Leonie Hagen

February 1, 2021

Detroit is an unusual place. Shaken by its economical downfall, abandoned by its own government, the city and her citizens had to learn to play by their own rules. A former industrial metropolis, previously referred to as the ‘Paris of the Midwest’ now finds itself being an allegory for urban crisis, abandonment and city dystopia.

On Nov. 29, 2018 the New York Times published an article titled: ‘In a ‘French Detroit’, a Housing Crisis Turns Deadly for Poor’ which covered the housing crisis in Marseille and depicted life in its slums 1. The Times later changed the title, removing Detroit from the headline; nonetheless Detroit has at this point in time become a shibboleth of failure.

When moving through the streets of Detroit, it very much feels like life is slowed down. A city so harshly stuck in the past when compared to other major cities of the Western World. Any progress appears to be nearly invisible to the public eye as the city moves forward at its own pace, recovering slowly. Nobody is in a rush, there is not a lot of traffic, not many people are in the city’s streets; you just don’t get that familiar buoyant big-city-vibe. Detroit feels like a place of solitude, vibrant at the same time but one has to know where to look. In a way it brings to mind J. M. Barrie’s creation of the Neverland, a place from which time is banned, used as a metaphor for immortality, endless youth and escapism.2 Of course Detroit very much depicts literal mortality though – buildings collapsing, cars falling apart, streets crumbling, people living in poverty – regardless, the conception of time doesn’t seem to grasp here quite like other places.

There are still plenty of souvenirs displaying the “good days” of the Motor City, telling the tale of a glamorous, wealthy long-gone Detroit. The fountain on Belle Isle, beautiful Art Deco highrises in Downtown, like the Guardian Building or the Penobscot Building (see figure 2), landmarks like the Fisher Building, just to name a few. Although those places are so fundamentally part of Detroit, it is hard to imagine this postcard-version of the city. They are ghosts of the past accompanying us in our rather dark present; monuments that capture the bright past of the city, turning Detroit into a new kind of Athens or Rome with its ‘ancient’ sights preserved amidst the contemporary, less glamorous city.

The presence of clocks in public spaces provides a tool for the people while also sort of marking an awareness of the city’s own participation in contemporary society. When being mindful of timekeeping devices in the cityscape of Detroit, there are a handful to be found. Mostly Downtown in the Financial District, some seemingly randomly scattered across the city attached to various kinds of buildings. Some on abandoned mediocre buildings, some on very iconic buildings. Some on banks, some on office buildings, some on shopping malls, some on churches. A few working, most out of order. Some of those still working are set at a wrong time. Nobody seems to care, clocks have vanished from the people’s consciousness.

Mechanical clocks first occurred around 1300 in Europe. They remained the principal time keeping device across the world until the digital age began in the mid-20th century; largely superseding previous tools to reckon time like sundials, water clocks, hour glasses and so forth. Looking at European cities, broadly speaking, clocks were to be found embedded into the turrets of churches or incorporated into the main façades of official buildings through to the late 19th century. Clocks reflected power, culture and were mainly placed at the center of cities, towns and villages, adding to the importance of those buildings.

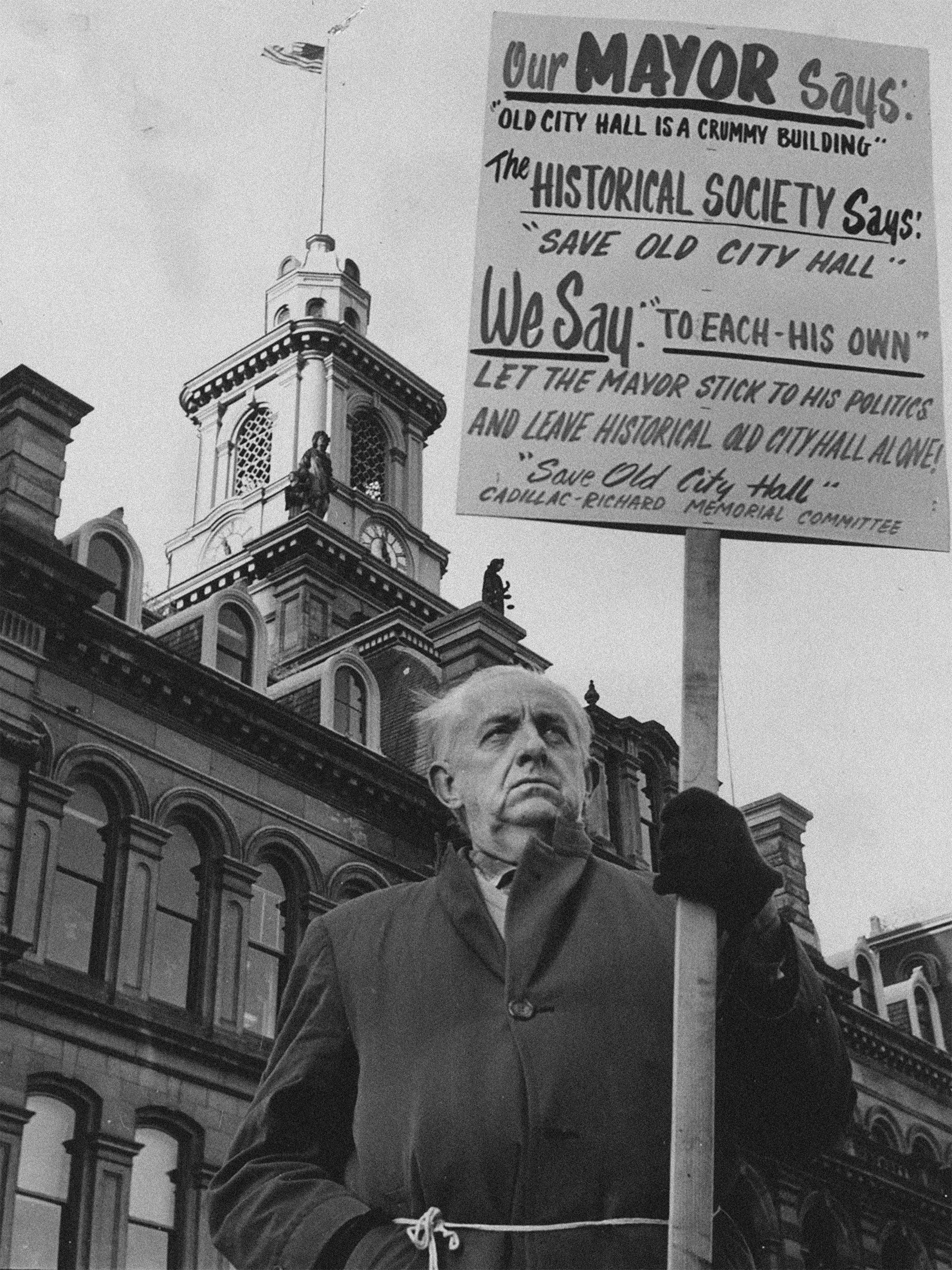

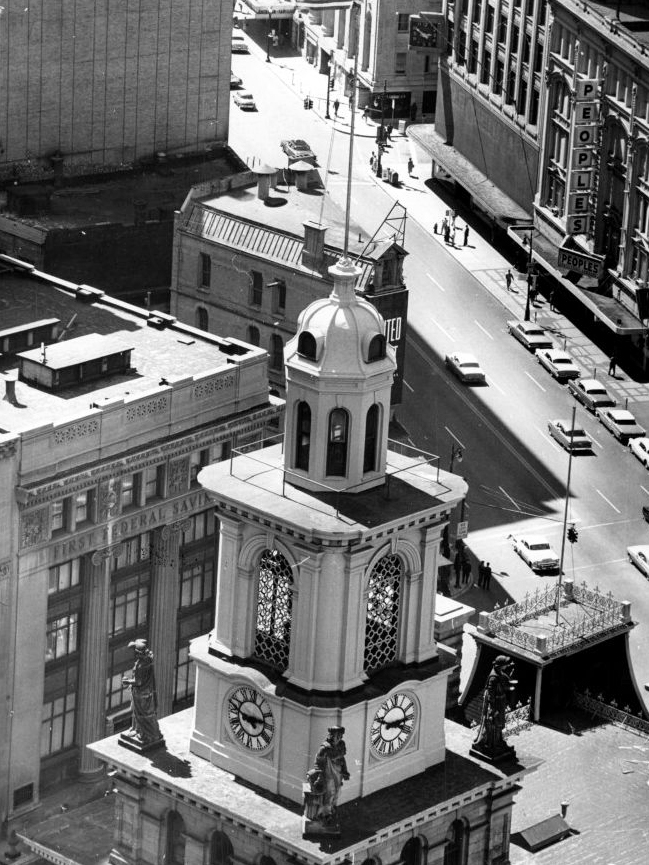

Historically, Detroit’s former City Hall (see figures 3, 4) was an important representative building in Downtown Detroit, at the focal point of city planning. It was a confident free-standing three-story solitary construction set on the west side of Campus Martius, referencing various European building styles. At its center, a huge clock tower, emphasizing its importance, at the top a massive American flag, marking it an official building, marking its importance within the cityscape. Clocks were on all four sides if the bell tower, directly relating time to power and government. Next to the clocks are four 14-foot statues representing justice, industry, art and commerce.

The building was finally demolished in 1961 after several attempts to get the demolition passed. From then on the Coleman A. Young Municipal Center was defined as the city and county’s new seat of government.3

When looking at the history of clocks in Detroit’s cityscape, a famous example is the Kern’s clock (see figure 5). It was restored recently and is still up and running but taken out of context. Originally it was located at the corner of Woodward Ave and Gratiot Ave, where it emphasized the main entrance to the Ernst Kern Company department store. ‘I’ll meet you under the Kern’s clock’ 4 was established as a common term. The building was demolished in 1966 but the clock was saved, restored and reinstalled near its original location as a freestanding object5.

Around the time when the Kern’s clock was originally included as part of the department store, there was a shift happening from religion and government at the center of cities and culture towards consumerism and capitalism.

Looking at buildings in downtown Detroit and beyond that are adorned with clocks, they are no longer buildings of religion and governance but buildings of commerce – with a few exceptions, of course, and time became no longer connected to culture and religion, but to money. Money has replaced religion. Time is money. In some cases you might even find a clock on a bank building, like the magnificent Savoyard Center (see figure 6), also known as State Savings Bank on 151 West Fort Street, erected in 1900 by the renowned New York architecture firm McKim, Mead and White.

In the late 19th century, the City Beautiful Movement arose, led by the upper-middle class concerned about the direction major cities in North America were heading in. The intent was to reform the architecture and urban planning of cities like Washington D.C., Chicago and Detroit, just to name a few. Their concern was that commerce disrupted a traditional hierarchy in which civic, cultural and religious buildings had previously dominated throughout the cityscape and skyline of those cities. The new canon of urban monumentality, with its warehouses, industrial structures, department stores and hotels, wasn’t a desirable way to define city centres in their opinion. The advocates of the movement were looking to bring beauty and grandeur to the inner cities, mainly looking at European cities as their sought after ideals. Boulevards and plazas were planned, adorned with statues, fountains and memorials.

By reconfiguring the urban landscape, they hoped to redefine public life and make people’s lives better as a consequence thereof. This movement was highly controversial and many urban planners and architects of the time were critical of it; Jane Jacobs for example titled it a mere “architectural design cult”6, that didn’t intend to solve any social issues really.

Coming back to Detroit, the main city planning focus of the movement was Woodward Avenue, specifically the so-called Detroit’s Center of Arts and Letters, led by Edward H. Bennett and Frank Miles Day with Cass Gilbert’s Detroit Public Library, opened in 1921, and Paul Cret’s Detroit Institute of Arts, opened in 1927, as its centerpiece 7. There are no clocks to be found in Detroit’s Center of Arts and Letters but the architectural style of this movement will deeply influence the developments that were going to happen around town in the next couple of years and even decades. Some examples: In 1923, the renowned Detroit architect Albert Kahn constructed the Cadillac Place building (see figure 7), formerly known as General Motors Building on West Grand Boulevard. On its main facade above the entrance: a clock embedded in an ornament. In 1923 as well, Alvin E. Harley erected the CPA building (see figure 8), home of the Conductors Protective Association on Michigan Avenue. Above its corner entrance: a clock embedded flush into its façade. In 1930, the neoclassical One Griswold was built, formerly known as the Standard Savings & Loan Building (see figure 9), purchased by the Church of Scientology in 2007, housing their Detroit Headquarters today. On the corner of Griswold Street and West Jefferson Avenue again a clock highlighting the building’s presence.

Another kind of architecture that time is inevitably connected to is the architecture of travel. The ghosts of the era, when train travel was exciting and celebrated by the American people, are occasionally still visible in the cityscape. From 1893 to 1971 the Fort Street Union Depot served the city of Detroit as a passenger train station. The station occupied the corner of Fort Street and Third Street and was eventually demolished in 1974. On a daily basis, hundreds of people arrived in Detroit on this block and would get their first impressions of the city starting from there 8. Before, another Depot just a couple of blocks away on the corner of West Jefferson Avenue and Third Street served as the city’s main railway station, the Michigan Central Railroad Depot, demolished in 1966. Both projects were defined by a corner tower with clocks embedded in each of their four façades9.

After the Michigan Central Station was erected in Corktown in 1913, the station became the main station of the city, superseding the other ones. The clock on the depot building east of the main building (see figure 10) next to the infamous station was anonymously returned after the Ford Company purchased the station in 2018 and declared the preservation and massive renovation of the significant structure10. The iconic Detroit building had been vacant for some 30 years and was slowly gutted over time, the clock being only one treasure someone took home. There’s no clock to be found anywhere close to the puny Amtrak station on West Baltimore Avenue – by the time this station was erected, the interest in train travel has largely vanished from the common American people and shifted towards air travel.

There are many more clocks still to be found across town; if you pay attention to it, you will start to see them. But with most of those clocks out of order, even on buildings that are still being used and maintained, what does this leave us with? Because they no longer function as the tools they are supposed to be, people have become oblivious to them altogether. They turn into just another part of the backdrop of fossils of the city’s past. It seems like although they are not working as time-keepers, they take on a new role as objects that actively assume a significant metaphorical power: they symbolize lost time, or time standing still, or the freedom to take time, to overcome the continuous urban race against time; enhancing the already abstract, floating sense of contemporaneity that is present all over the city today. What to make of a world without clocks?

1. Adam Nossiter, “In a ‘French Detroit’, a Housing Crisis Turns Deadly for Poor,” New York Times, November 19, 2018. Link.(accessed Nov. 20, 2018 and Dec. 28, 2020)

2. Wikipedia. “Neverland.” Last modified December 29, 2020

3. Dan Austin, “Old City Hall” Historic Detroit, https://historicdetroit.org/ buildings/union-depot. (accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

4. Phoebe Wall Howard, “Thief Returns Train Station Clock, Thanks Ford for Believing in Detroit,” Detroit Free Press, June 19, 2018. Link.(accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

5. “Earnst Kern Company,” Link.(accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

6. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), p. 375

7. Daniel M. Bluestone, “Detroit’s City Beautiful and the Problem of Com- merce,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, No. 3 (1988): p. 245-262. Link.(accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

8. Dan Austin, “Union Depot,” Historic Detroit, Link.(accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

9. Dan Austin, “Michigan Central Railroad Depot,” Historic Detroit,Link. (accessed Dec. 28, 2020)

10. Jonathan Marcus, “Michigan Central and the rebirth of Detroit”, BBC News, Link. (accessed Dec, 28, 2020)